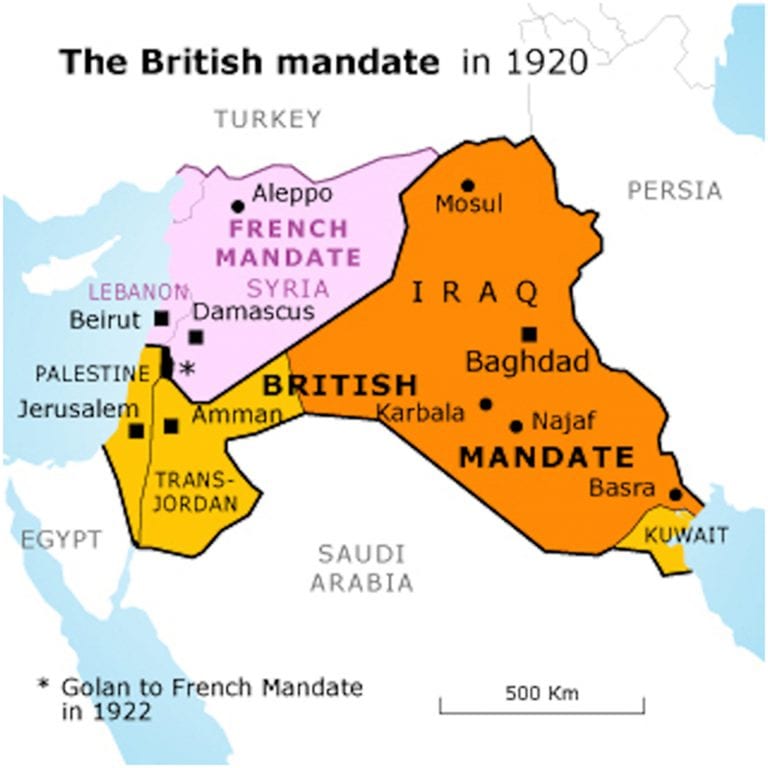

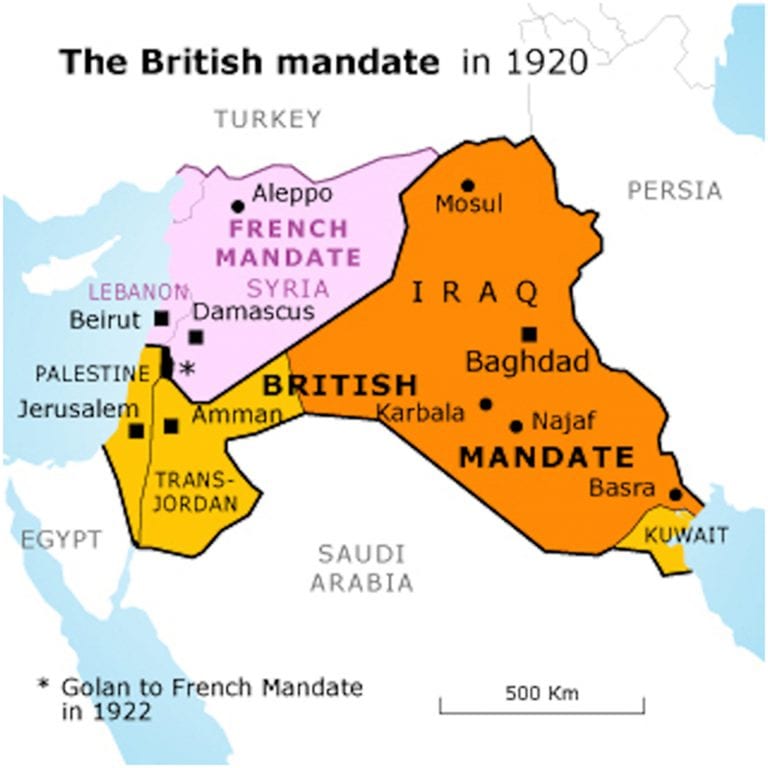

One hundred years ago this week, the modern Middle East came into being.

On 19 April 1920, the leaders of the allied victors of World War 1 gathered at the Italian Riviera town of San Remo. Their task was to decide the future of the vast territories of the Middle East ruled since 1517 by the defeated Ottoman Empire.

This huge area of more than 700,000 square km was thinly populated by people of predominantly Arab culture and Muslim religion, but with many minorities of different ethnicities – Kurdish, Turkmen, Circassian – and religious faiths – Shia and Sunni Muslim; Assyrian Church, Chaldean Catholic, Syriac Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, Greek Catholic and Maronite Christian; Jewish, Druze, Yazidi, Alawite and Ahmadiyya.

The conference took place against the background of demands from Arab political leaders for the establishment of an independent Arab state, and of Zionist Jews for a national homeland for the Jewish people in their ancestral land.

The conference agreed on a proposed treaty dealing with the borders of Turkey itself, to be later signed at Sèvres in August 1920. It provided for an independent state for the Armenian people (the victims of the Ottoman genocide of the 1890s and 1915-21), and an autonomous state for the Kurdish people. Because of renewed war in Turkey, those provisions were never implemented. To this day, the Kurdish people are without a state and the historic western Armenian lands are still under Turkish rule.

The British Mandate was also tasked with implementing the Balfour Declaration of 2 November 1917, adopted by the other Allied Powers: ‘the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country’.

In September 1922, the League of Nations approved the exclusion of the area east of the river Jordan – Transjordan (77 per cent of the Mandate) – from the clauses relating to Jewish settlement. In the remaining 23 per cent of the territory, i.e. the land between the river and the sea, the British governors were obliged to ‘facilitate Jewish immigration under suitable conditions and encourage close settlement by Jews on the land’. That right of Jews to settlement was incorporated into Article 80 of the United Nations Charter in 1945 and has never been revoked. However, the UN General Assembly voted in November 1947 to partition this area into two states, Jewish and Arab.

From the French and British Mandates have evolved the five modern states of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Israel. The first four are Arab states belonging to the global family of 22 Arab states, having a total area of 722,046 square km and a combined population of 82 million. The fifth is the world’s single Jewish state, with an area of 22,145 square km (three per cent of the total) and a population of 9 million (10 per cent of the total). However, due to the violent refusal of Arab leaderships to recognise the 1947 partition plan, the Palestinian Arab state has not materialised.

*************************

A brief look at the subsequent histories of the five successor states of the Ottoman Empire should allow us to assess their comparative success as modern polities in the light of criteria such as achievement of democratic government, peaceful transition of power, safeguarding of human rights and protection of the rights of minorities.

Iraq, the first to gain independence in 1932, began life with its army launching horrific massacres against the Assyrian Christian minority, slaughtering 6,000 of them. In 1941, a violent pogrom – the ‘Farhud’ – erupted against Baghdad’s 2,500-year-old Jewish community. At least 18o Jews were slaughtered and 1,000 injured by rioters, who looted over 500 Jewish businesses and destroyed 900 homes. The Farhud marked the beginning of the exodus of Iraq’s Jewish population. Subsequent years saw a succession of military coups, ending with takeover by Saddam Hussein. Saddam’s tyrannical rule was marked by the devastating Iraq-Iran war (1980-88) which caused at least a million deaths; poison gas attacks on the Kurds and the 1990 invasion of Kuwait that triggered war with the US. Since then we have seen western intervention to protect the Kurds and Shia, the Coalition invasion of Iraq and the descent into Sunni-Shia sectarian war. US withdrawal in 2011 was followed by the rise of ISIS with its barbaric Islamic caliphate, in huge swathes of Iraq and Syria, enslaving and massacring tens of thousands including over 5,000 Yazidis.

Itself newly independent, Jordan was one of the five countries that invaded the newborn state of Israel on 15 May 1948. Its Arab Legion captured the West Bank (historic Judea-Samaria) and eastern Jerusalem, expelled the Jewish population, dynamited almost all synagogues there and desecrated the Mount of Olives cemetery. In 1967, King Hussein declared war again on Israel and shelled Jewish western Jerusalem. The ensuing Israeli victory in the Six Day War liberated eastern Jerusalem and brought the West Bank under Israeli control. Since then, the country has been (relatively) peaceful. The monarchy signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1994.

From its beginning in 1943, the state of Lebanon lived in a precarious equilibrium of mutually suspicious ethnicities and religious sects – Maronite Christians, Sunni and Shia Muslims and Druze. In 1975, sectarian tensions boiled over; the disastrous 15-year civil war caused an estimated 120,000 fatalities with a million fleeing the country. The state is now held hostage by Hezbollah, a terrorist proxy of Iran. With an arsenal larger than that of the official Lebanese army, including tens of thousands of rockets trained on Israel, Hezbollah threatens to drag the country into war at any moment.

Syria’s history from independence in 1946 was characterised by a long series of military coups. In a permanent state of war with Israel since 1948, it suffered three humiliating military defeats and the loss of the Golan Heights. Finally, the Ba’athist Hafez al-Assad seized power in 1970. Assad’s rule is remembered for its support of Iran in the Iraq-Iran War; the brutal 1982 crushing with tanks and artillery of the Muslim Brotherhood revolt in the city of Hama with an estimated 15,000-20,000 deaths; and the imprisonment and torture of political dissenters. The rule of Assad’s son, Bashir al-Assad, has been dominated by the catastrophic Syrian civil war (2011 to date) and its atrocities that have generated the worst humanitarian crisis since World War 2 and a death toll estimated at somewhere between 500,000 and 600,000.

Finally, we come to Israel. Founded as a parliamentary democracy in 1948, it has faced the task of absorbing tens of thousands of displaced Holocaust victims and 900,000 Jewish people expelled from Arab countries. It has faced three conventional wars aimed at its annihilation, prolonged campaigns of terrorism, and the firing of more than 15,000 rockets on its southern territory from the Gaza Strip since its evacuation from there in 2005. It faces regular ongoing threats of destruction by the Iranian regime, which arms the two terrorist forces, Hezbollah and Hamas, that threaten its cities with their rocket arsenals. It faces vigorous campaigns of boycott and ‘lawfare’ abroad aimed at delegitimising its existence and its right to defend itself. In spite of these challenges, it has continued to thrive as a democratic state with a vibrant parliament and electoral system, guaranteeing full civil and religious rights to its 21 per cent Arab minority (the only Arabs in the entire Middle East enjoying those rights). It has concluded lasting peace treaties with former enemies Egypt and Jordan, returning huge tracts of land to the former, and has made many (rejected) offers of statehood to the Palestinian Arabs. In the disputed lands of the West Bank it has found creative ways to balance the Jewish right of settlement with the right of the Arab population to self-government and its own strategic defence needs in a region where Islamic culture dictates that a non-Muslim state, however small, cannot be allowed to exist on land once ruled by Islam. And, in the midst of these enormous challenges, it shines forth as a hub of cultural brilliance, medical excellence and technological innovation.

The notion that Israel is the fundamental cause of all insecurity and violence in the Middle East is pervasive in our media and politicians. This survey of its neighbourhood, a hundred years after San Remo, should be sufficient evidence that, far from being the problem in the Middle East, Israel is the role model for its neighbours to follow, if only there were willing emulators.

By Dermot Meleady