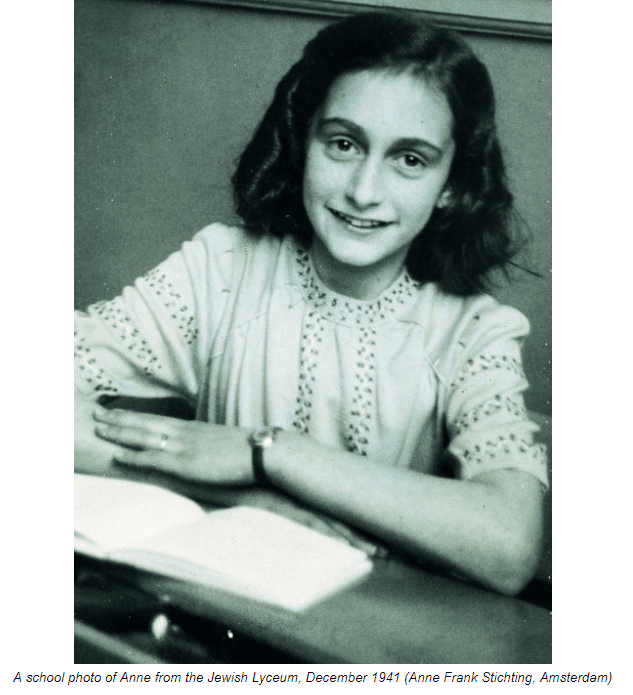

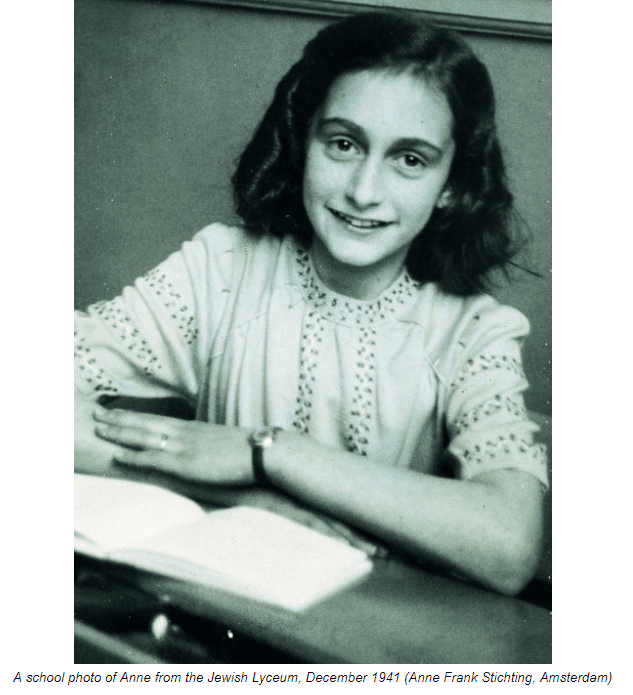

Anyone who has read The Diary of Anne Frank will have been struck by the determination of that teenage girl to never despair, and to still cling to hope in the face of so many tribulations.

If you have ever visited the achterhuis (Dutch for “backhouse”) in the Anne Frank Museum in Amsterdam, you will have been struck by how small it is. It was here that Otto Frank, his wife Edith, two daughters (Margot and Anne), and four other Jews had refuge from the horrors of Nazi persecution. This writer has been there twice and on each occasion found himself wondering how eight people from three different families could have shared this roughly 40 square metre area for over two years from 1942 to 1944.

Anne Frank was born in Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany in 1929. Her family fled to the Netherlands in the early 1930s when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party came to power. Otto’s brother-in-law, Erich Elias, worked in Switzerland for a company called Opekta selling spices and the pectin gelling agent that was used in jam manufacture. Fortunately for Otto and his family, the company was looking to expand its operations in other countries so Erich arranged for Otto to set up and work as the head of the company’s new Dutch subsidiary in the Netherlands. The Franks moved to Amsterdam knowing that they would have an income there while being safe from the Nazi horror.

Family’s fortunes initially improve

In the safety of the Netherlands, the family’s fortunes initially improved. A few years later in 1938, Otto Frank started a second company called Pectacon, which was a wholesaler of herbs, pickling salts, and mixed spices, used in the production of sausages. However, Germany invaded the Netherlands in May 1940 and the Frank family found themselves in danger all over again. The new Nazi regime forbade Jews from owning businesses so Otto Frank had to “aryanise” his two companies – effectively transferring control of them to his non-Jewish employees.

The headquarters of Otto’s Opekta company were at 263 Prinsengracht (along one of Amsterdam’s famed canals) and it was there that his family fled on July 6th 1942 when it became clear that the Nazis were beginning the mass deportation of the Jewish population. The day before, Anne’s older sister, Margot, had received a written summons to report for “labour duty” in Germany, and the family realised that they had to move quickly. With the help of a few Dutch friends who were employees in Otto’s company, they installed themselves in the small annex at the back of the company offices.

Two years at 263 Prinsengracht

A week later, the Franks were joined by another family of Jews who had fled Germany: Hermann van Pels, his wife Auguste and their teenage son, Peter. The following November, Fritz Pfeffer, a Jewish dentist whose family had had to leave Germany also moved in. There, those eight people were to remain for over two years, hiding from the horror that was engulfing the Dutch Jewish community.

You can take a look around the achterhuis at this link on the Anne Frank Museum website. Choose Step Inside, then Explore this Room on the following page and then click on the red door symbol on the bookcase to get into the annex. One can only imagine the sense of claustrophobia, the lack of privacy, and the frustrations of so many people from different families living in such close quarters for nearly 800 days. Above all, there was always the fear of being discovered by the Nazis and being deported to the death camps.

Hope filters through

And yet, the families were not completely cut off from the world. They had access to a radio and would have known about the series of reverses that the Axis powers had begun to experience from late 1942 in North Africa and the Pacific, the Eastern Front at Stalingrad in early 1943, and Italy in late 1943. They also had their Dutch friends (especially Miep Gies) who went to heroic lengths to procure food for them while not attracting the attention of the authorities and who, no doubt, kept them informed of what was going on outside the tiny confined space of the achterhuis.

Anne wrote in her diary of hearing about D-Day on BBC radio on June 6th 1944: “Is this really the beginning of the long-awaited liberation? The liberation we’ve all talked so much about, which still seems too good, too much of a fairy tale ever to come true? Will this year, 1944, bring us victory? We don’t know yet. But where there’s hope, there’s life.”

The families are seized

Imagine then the terror and the crushing sense of disappointment fewer than 2 months later and 77 years ago today when on August 4th 1944, the achterhuis was stormed by a group from the Nazi Grüne Polizei. This means ”Green Police”, a name related to their green uniforms.All eight residents were captured and two days later on August 6th, they were sent to the Westerbork transit camp and forced to do hard labour.

Approximately one month later, the group was transported to the Auschwitz concentration camp in what is now modern-day Poland but was then, of course, still under the control of the Nazis. Thereafter – given that men and women were separated – Anne, along with her sister and mother lost contact with their father and may have believed that he had been murdered by gassing, given that he was not in very good health.

The female members of the group were forced to engage in harsh physical labour, digging the hard soil and hauling large rocks, while being provided with only starvation rations. In late October 1944, with the advance of Soviet troops. many of the prisoners were selected for relocation to Bergen-Belsen, another death camp to the west and further behind Nazi defence lines in Germany. More than 8,000 women, including Anne and Margot Frank, and Auguste van Pels, were transported to Bergen-Belsen. Edith Frank, was left behind and was starved to death.

The miserable conditions already pertaining in Bergen-Belsen were vastly worsened by the influx of starving, diseased prisoners from Auschwitz. The unsanitary conditions enforced by the Nazis and the diet which was designed for the starvation to death of the prisoners were ideal conditions for the outbreak of disease. There was a typhus epidemic in the early months of 1945 which killed approximately 17,000 prisoners.

Anne’s words of hope

Anyone who has read The Diary of Anne Frank can’t fail to have been struck by the determination of that teenage girl to never despair, to still cling to hope in the face of so many tribulations, to reject the belief that the world was hopelessly evil, to refuse to abandon the idea that she (or any of us!) could be an active agent (however insignificantly) in making this little, blue and green planet into a better place for all.

How wonderful it is that nobody needs to wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.

[…]

Everyone has inside of him a piece of good news. The good news is that you don’t know how great you can be! How much you can love! What you can accomplish! And what your potential is!

[…]

Whoever is happy will make others happy too.

[…]

I don’t think of all the misery but of the beauty that still remains.

Anne Frank could never have known that anyone else would ever find her diary and read her words. She wonders at one point, “Who else but me is ever going to read these letters?” She had no followers, no-one to provide that affirmation of a like, or a share or retweet. The words were almost certainly written by her solely to be read again by her at times when she needed to be raised up from the darkness and despair that was all-encompassing and ever-pressing.

The contrast with today’s social media-driven world couldn’t be starker. On Facebook and Twitter we have far too many “influencers” who will quite literally say anything – however risible or outrageous – to garner more popularity from their followers. There is no argument that is too ridiculous, no point of view too laughable, no assertion too patently at variance with all available and verifiable facts to not be tweeted and shared.

One example is the widespread use of analogies with Naziism; a certain action or policy is likened to what Nazis would have done or possibly even worse than what they would have done. A particular instance of this is recent comment about the measures various governments have been taking either to deal with the COVID19 pandemic or to reopen society as more and more people have been vaccinated. Such comparisons are not just ahistorical nonsense; they also serve to minimise the unique horror and evil of the Holocaust which is only one step away from Holocaust denial.

What would Anne say to such people? Of course, we’ll never know. It’s believed that she passed away along with her sister Margot during the typhus epidemic in Bergen-Belsen sometime in February or March 1945. The only surviving member of the eight who sheltered for over two years in the achterhuis was Otto Frank. Instead, let us end with one final uplifting quote from her diary as a reminder of how – against all the evidence – she strove to see the positive in everything and everyone.

It’s difficult in times like these: ideals, dreams and cherished hopes rise within us, only to be crushed by grim reality. It’s a wonder I haven’t abandoned all my ideals, they seem so absurd and impractical. Yet I cling to them because I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.

By Ciarán Ó Raghallaigh